O Saint Bernadette you who as a meek innocent child were privileged to see eighteen times the Immaculate Mother of God and to be instructed by Her with many heavenly messages and who as a religious at the Convent of Nevers did offer yourself as a victim for the Conversion of sinners, obtain for us the grace to be pure of heart and to love mortification as you did, that we may be found worthy to see God and His Holy Mother in Heaven. Amen.

Prayer on the Feast Day of St. Bernadette

O God, protector and lover of the humble, Who has bestowed upon Thy servant, Marie Bernadette, the favor of beholding the Immaculate Virgin Mary and of conversing with her, grant, we beseech Thee, that walking through the simple paths of faith, we may deserve to behold Thee in heaven. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, Thy Son, Who liveth and reighneth with Thee in the unity of the Holy spirit, God, world without end. Amen.

________________________________

St. Bernadette and Her Visions of Our Lady

by Richard F. Clarke, S.J., 1888

Many of my readers are probably familiar with M. Lasserre's picturesque account of the appearance of Our Lady to Bernadette, and of the early history of the Grotto at Lourdes. If I had nothing more to tell, I should hesitate about writing the story of that favored child of Heaven. But years have passed since M. Lasserre devoted his skilful pen to the service of Our Lady of Lourdes. Bernadette's work is over, and she has gone to behold forever, face to face, the dazzling beauty of the Queen of Heaven, who deigned to manifest herself to her by the flowing waters of the Gave. Time, that tries all things, has tried the truth of Bernadette's story, and every succeeding year has rooted more deeply in the minds of Catholics all over the world the conviction that it was Our Lady herself who, in her condescending love, deigned to appear to the poor peasant girl of Lourdes.

The words of Our Lady to her respecting her own future history have been exactly verified, and perhaps one of the most curious confirmations of the reality of the appearances to Bernadette is that she lived and died obscure and unknown; that in the convent where her latter years were spent she was a continual sufferer; that there she lived the most ordinary, matter-of-fact, commonplace life; and that up to the moment of her death, she never pretended to any sort of extraordinary favor, or vision, or revelation after the last appearance by the Grotto. If the miracles that have been worked there had never happened, there is sufficient evidence in the conduct of Bernadette to establish in the minds of any impartial witness the truth of what she saw. But we are anticipating, and must leave our readers to judge of the facts narrated as we proceed.

The words of Our Lady to her respecting her own future history have been exactly verified, and perhaps one of the most curious confirmations of the reality of the appearances to Bernadette is that she lived and died obscure and unknown; that in the convent where her latter years were spent she was a continual sufferer; that there she lived the most ordinary, matter-of-fact, commonplace life; and that up to the moment of her death, she never pretended to any sort of extraordinary favor, or vision, or revelation after the last appearance by the Grotto. If the miracles that have been worked there had never happened, there is sufficient evidence in the conduct of Bernadette to establish in the minds of any impartial witness the truth of what she saw. But we are anticipating, and must leave our readers to judge of the facts narrated as we proceed.

Bernadette was the child of two pious peasants who lived near the Grotto of Lourdes, very poor, but very honest and simple. She was rather below the average in intelligence, but largely endowed with that candor and innocence of soul that God loves.

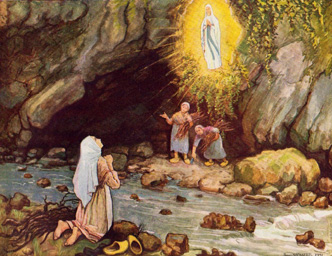

On February 11, 1858, when Bernadette was fourteen years old, she was sent with her sister, Marie, and another companion, to pick up for firing pieces of wood that had floated down the stream, and that were wont to drift into the shore just under the Grotto of Massabielle. To reach the spot, it was necessary to cross the bed of the mill-stream, which flowed into the Gave, and which was then almost empty of water, because of the repairs going on at the mill. Her two companions had doffed their wooden clogs and crossed the little stream. Bernadette, who was rather delicate, and wore stockings, waited behind to take them off. She was leaning up against a rock to do so, when she heard a sound as of a rushing wind. She looked up at the trees, but to her surprise their branches were not moved by it.

She then turned towards the Grotto, and noticed that a magnificent wild rose-tree, or briar, which was rooted in a niche in the rock, and the branches of which hung down to the ground, was being gently shaken.

On February 11, 1858, when Bernadette was fourteen years old, she was sent with her sister, Marie, and another companion, to pick up for firing pieces of wood that had floated down the stream, and that were wont to drift into the shore just under the Grotto of Massabielle. To reach the spot, it was necessary to cross the bed of the mill-stream, which flowed into the Gave, and which was then almost empty of water, because of the repairs going on at the mill. Her two companions had doffed their wooden clogs and crossed the little stream. Bernadette, who was rather delicate, and wore stockings, waited behind to take them off. She was leaning up against a rock to do so, when she heard a sound as of a rushing wind. She looked up at the trees, but to her surprise their branches were not moved by it.

She then turned towards the Grotto, and noticed that a magnificent wild rose-tree, or briar, which was rooted in a niche in the rock, and the branches of which hung down to the ground, was being gently shaken.

All of a sudden, around the niche, an oval ring of brilliant golden light appeared, and within the niche she saw standing a Lady of unspeakable beauty, with her feet, which were covered by two large roses (1), resting lightly on the wild rose-tree. She was dressed in pure white, with a light blue girdle; a white veil covered her head, and on her arm was hanging a rosary with a cross of gold. The Lady, as if to encourage Bernadette, made a big sign of the Cross with the cross at the end of the rosary, and began to pass the beads through her fingers. The child, half frightened, yet conscious of the presence of something supernatural and Divine, fell on her knees, and instinctively took the rosary she had with her, made the sign of the Cross, as did her celestial visitor, and said her beads. When she had finished, the vision was gone.

She arose, and ran after her companions. "Have you seen anything?" she asked.--"No," they had seen nothing. "And you?"--Bernadette knew not what to answer, but after they had made up their little bundle of sticks, and were on their way home, they noticed something strange about her, and she told them the story in all simplicity. Arrived at home, they told her mother, who scolded her for talking nonsense, and ordered the children not to go to the Grotto to pick up their wood.

From the moment that the vision had disappeared, Bernadette had been longing to see it again, but she obeyed her mother, and kept away from the place. But her sister and some of their little neighbors, moved by curiosity, persuaded their mother to withdraw her prohibition, and allow them to go there on the next Saturday. The children, who knew that evil spirits sometimes appear and deceive men, agreed that they would take with them some holy water. Thus armed, they went to the Grotto, knelt down, and began their rosary. They had scarcely commenced it, when Bernadette's countenance was suddenly transformed, her features seemed to be lit up with a light from Heaven: there was an expression in her face of unspeakable joy and happiness. In general she was a very ordinary sort of child, but now there was something extraordinary and supernatural in her expression. She saw the same beautiful Lady, with her feet resting on the rock, in the same niche as on the previous occasion, dressed in just the same manner, and surrounded by the same circle of golden light. Beaming with joy, she exclaimed to her companions, "There she is!" But the other children, whose eyes were not opened as were Bernadette's, saw nothing but the bare rock and the wild rose-tree. But yet they did not doubt about the apparition to Bernadette, and one of them placed in her hands the bottle of holy water. The child took it, advanced a step, and throwing some holy water towards the Grotto, cried out, " If you come from God, come nearer! " At these words, the Lady smiled, and advanced to the very edge of the rock, as if to meet Bernadette, who thereupon, reassured by her advance and by the gracious expression of her face, fell on her knees as before, and said the rosary as before. When it was over, the vision disappeared at once.

The report of this second apparition soon spread throughout the town, and people came to the house of the Soubirous and cross-questioned Bernadette. Her precise and unhesitating answers astonished them. It was enough to see and hear her to be convinced of her good faith.

On the following Thursday, the 18th of February, two good women of the neighborhood, anxious to convince themselves of the truth of her story, offered to accompany her to the Grotto. "Ask the Lady," they said, "who she is and what she wants; let her explain it to you, or better still, as you may not understand very well what she means, ask her to write it down for you." On the road to the Grotto the child, in her eagerness, got ahead of her companions, arrived at the Grotto, knelt down in front of it with her eyes upon the niche, and began to say her beads. She was thus employed when her companions arrived. All at once a cry of joy escapes her lips: "There she is!" she exclaims. The expression of her features changes: her face lights up with the same heavenly brightness as before: no one can doubt that she is in the presence of something mysterious, unseen by others, and that she is experiencing an extraordinary joy and happiness. The two women kneel down by her side and light a blessed candle that they have brought, then they produce their pen and ink: " Go up to the Lady," they say, " and ask her to write down who she is and what she wants."

Bernadette, not a bit afraid, went right up to the wild rose-tree in which Our Lady was standing, held up her paper and ink bottle, and stood there looking up at the niche. Our Lady smiled. " It is not necessary to write down what I have to say to you. Do me the kindness to come here every day for a fortnight." "Yes, I will," said Bernadette. Then Our Lady added: " And on my part, I promise to make you happy, not in this world but in the next."

Strange promise, that no girl of fourteen would have invented! Promise, too, strangely fulfilled. As we shall see, Bernadette's life was not what we should call a happy one. All her life long she was the victim of continual ill-health. Her chest was weak; she had a chronic asthma, which often caused her most intense suffering, and as she grew up a large tumor formed on her knee, and her bones were attacked by caries. She had also all sorts of external crosses and persecutions to endure, and, moreover, in her own soul there was, to the very end, little of joy and internal consolation. Hers was a dull, monotonous, struggling existence till the very day of her death; matter of fact from first to last, with none of that excitement or enthusiasm, such as is wont to accompany fancied visions and celestial visitations, sprung of an overwrought imagination.

"Ask her," said one of Bernadette's companions, "if she minds our coming with you." "No," was the reply, "they may come if they like." Then the vision disappeared. When the child returned to the town she told her parents that the Lady had made her promise to come to the rock every day for a fortnight. The next day her mother went with her, and a number of other women accompanied her. They all noticed the same wonderful expression that came over the child's features as soon as Our Lady appeared to her.

During the next few days the number of spectators increased. The story spread from mouth to mouth. No one would think that the child was trying to deceive them. She might be under an illusion, the victim of a highly-wrought imagination, but she was no impostor. It was wonderful to see her as she knelt day by day amid the crowd, with a taper in one hand and her rosary in the other, while a religious silence prevailed. Some mysterious influence secured and held all present spellbound. After a few days there was a crowd of some thousands present at the scene long before sunrise. All the best points of observation were occupied by spectators, in spite of the piercing cold. What strange attraction could there be in watching a poor peasant girl kneeling and saying her beads?

Each morning was the same: an increasing crowd, praying, chattering, waiting, struggling for a good place. Then all at once there was a movement in the crowd. "Here she comes!'' and Bernadette walks through the midst of them. They make a way for that poor, humble, insignificant peasant girl, with marks of the greatest respect, the men uncovering their heads as she passes. After her the crowd closes up and follows her, noisy and struggling, till she reaches the Grotto, where she kneels down on a flat piece of rock surrounded by sand, which is always left free, however great the throng, as "Bernadette's place." Then she kneels down and all eyes are fixed upon her. She begins her rosary as if there were no one there. All at once she raises her hands: her appearance changes: the indescribable expression creeps over her face, and a murmur breaks from the crowd, " now she sees her! "Meanwhile she continues her rosary, while those present gaze on her entranced. Her eyes are fixed on the niche in the rock: a sweet smile spreads itself over her countenance, on which love, admiration, joy, respect mingle together, and testify to the presence of one who to the kneeling throng around is invisible. From time to time tears like great drops of dew roll down her cheeks, tears of intense joy, bearing witness to a new, indescribable, and delicious happiness.

What did she see? First of all a soft light illuminating the niche and the rock, then an increasing brightness, then, over the wild rose-tree, appeared the Lady. A Lady of wondrous beauty, with all the freshness of early youth combined with the tenderness of a mother, of unspeakable benevolence in her looks, and a majesty which cannot be described. "Was the Lady as beautiful as certain ladies of remarkable beauty who had come to see her?" The child looked at them with a sort of disdain: "Ever so much more beautiful than they! The Lady, moreover, was surrounded with a circle of light." "What sort of light? Was it like the light of a large fire, or of the stars, or of the moon, or of the sun dazzling us in its mid-day glory?" "No, there was no light on earth resembling it; it was quite different from these and far more beautiful."

During the time of her ecstasy Bernadette saw nothing and heard nothing of what went on around her. If the crowd grew noisy and impatient she was not conscious of it. During that hour of Our Lady's presence she was deaf and blind to all save the vision of the Queen of Heaven.

One day the wind threatened to put out Bernadette's candle; instinctively she put up her hand to shelter the flame. All of a sudden a sweeping gust turned it towards her open hand and the flame passed between her fingers.

"Shell be burnt, poor child!" said the bystanders in pity. But there was not a sign of pain on her face or any shrinking movement of her hand. The fire left no trace: it had not harmed her.

In her ordinary state, Bernadette did not seem to be much preoccupied with this daily favor granted by God to her. She said but little about it, and her parents did not ask her many questions. But when the hour of the apparition drew near, she seemed to be in the possession of a power superior to her own, and the attraction to the Grotto became irresistible. Go to the Grotto she must. When her parents, urged by the police, as we shall presently see, asked her not to go, she told them she could not help going. At last they positively forbade her visits to the Grotto, and on the 22nd she reluctantly obeyed. In the morning she attended the parish school as usual, but in the afternoon she could not resist the secret influence of within that called her, and she went down to the Grotto. As usual she knelt down and said her rosary, but the Lady visited her not.

After this, in reply to threats and prohibitions, she calmly answered, " I can't promise you not to return to the Grotto; something tells me I ought to go; it drives me thither. I must follow the impulse within me." Her parents, recognizing in the influence that urged her one to which they were bound to submit, made no further opposition, Henceforward her mother generally accompanied her to the Grotto.

The next day (Tuesday, the 23d of February), the crowd came down as usual to the banks of the Gave. Bernadette appeared in due time, knelt down with a lighted taper in her hand, and began to say her beads. On this day Our Lady had two communications to make to her--one was a secret message concerning herself which she was told never to reveal, the other was a command which was to be obeyed in a way that even Bernadette never expected. "Go" said Our Lady, "to the priests, and tell them that it is my wish that they should build me a chapel here, and that they ought to come here in procession."

Who that gazes at the magnificent basilica that now adorns the rock of Massabielle, and watches the thousands of picas pilgrims streaming along the road to the Grotto in solemn procession, can fail to recognize the power of Mary's word? Her fiat, now as ever, echoes in Heaven and is obeyed on earth.

One of the following mornings witnessed a new feature in the apparitions. As Bernadette knelt in her ecstasy amid the assembled crowd, all at once she was seen to kiss the ground and then drag herself along on her knees towards the niche, touching the earth from time to time with her lips. She dragged herself up the steep ascent in front of the Grotto, entered it, and remained for a short time immovable, looking up in the direction of the niche. Then she turned to the crowd, drew herself up to her full height, and with wonderful authority and energy cried out:

"You, too, are to kiss the ground!"

Then she knelt down again, and herself set the example. What had Our Lady said to her? She had heard these words, "You will pray God for sinners; you will kiss the earth for the conversion of sinners,"

On several subsequent mornings the, same command was given to Bernadette. On these occasions she described Our Lady's countenance as veiled in an expression of infinite sadness, which, however, did not mar her look of perfect happiness and joy. Once the child kept murmuring, "Penance, penance, penance!" but in general she remained silent throughout her ecstasy.

Thursday, the 25th of February, was one of the most notable days in the history of the Grotto. All of a sudden, in the midst of her ecstasy, she moved as if summoned somewhere, and rising turned her steps towards the corner of the Grotto. Our Lady had said to her: "Go and drink in the spring and wash yourself there, and eat some of the little plant growing there."

The child had seen no spring, and thought it was meant that she should go to the Gave. But with her eyes and her outstretched arm Our Lady pointed to the corner of the Grotto. Bernadette accordingly began to move thither, while the crowd made way for her. A mass of sand and rock blocked up the entrance, and sloped upwards until the level within was six feet above the level of the earth without. She mounted the slope and looked for the spring. But spring there was none, not even a drop of water--only the moist ground with some herbs growing in it.

She arose, and ran after her companions. "Have you seen anything?" she asked.--"No," they had seen nothing. "And you?"--Bernadette knew not what to answer, but after they had made up their little bundle of sticks, and were on their way home, they noticed something strange about her, and she told them the story in all simplicity. Arrived at home, they told her mother, who scolded her for talking nonsense, and ordered the children not to go to the Grotto to pick up their wood.

From the moment that the vision had disappeared, Bernadette had been longing to see it again, but she obeyed her mother, and kept away from the place. But her sister and some of their little neighbors, moved by curiosity, persuaded their mother to withdraw her prohibition, and allow them to go there on the next Saturday. The children, who knew that evil spirits sometimes appear and deceive men, agreed that they would take with them some holy water. Thus armed, they went to the Grotto, knelt down, and began their rosary. They had scarcely commenced it, when Bernadette's countenance was suddenly transformed, her features seemed to be lit up with a light from Heaven: there was an expression in her face of unspeakable joy and happiness. In general she was a very ordinary sort of child, but now there was something extraordinary and supernatural in her expression. She saw the same beautiful Lady, with her feet resting on the rock, in the same niche as on the previous occasion, dressed in just the same manner, and surrounded by the same circle of golden light. Beaming with joy, she exclaimed to her companions, "There she is!" But the other children, whose eyes were not opened as were Bernadette's, saw nothing but the bare rock and the wild rose-tree. But yet they did not doubt about the apparition to Bernadette, and one of them placed in her hands the bottle of holy water. The child took it, advanced a step, and throwing some holy water towards the Grotto, cried out, " If you come from God, come nearer! " At these words, the Lady smiled, and advanced to the very edge of the rock, as if to meet Bernadette, who thereupon, reassured by her advance and by the gracious expression of her face, fell on her knees as before, and said the rosary as before. When it was over, the vision disappeared at once.

The report of this second apparition soon spread throughout the town, and people came to the house of the Soubirous and cross-questioned Bernadette. Her precise and unhesitating answers astonished them. It was enough to see and hear her to be convinced of her good faith.

On the following Thursday, the 18th of February, two good women of the neighborhood, anxious to convince themselves of the truth of her story, offered to accompany her to the Grotto. "Ask the Lady," they said, "who she is and what she wants; let her explain it to you, or better still, as you may not understand very well what she means, ask her to write it down for you." On the road to the Grotto the child, in her eagerness, got ahead of her companions, arrived at the Grotto, knelt down in front of it with her eyes upon the niche, and began to say her beads. She was thus employed when her companions arrived. All at once a cry of joy escapes her lips: "There she is!" she exclaims. The expression of her features changes: her face lights up with the same heavenly brightness as before: no one can doubt that she is in the presence of something mysterious, unseen by others, and that she is experiencing an extraordinary joy and happiness. The two women kneel down by her side and light a blessed candle that they have brought, then they produce their pen and ink: " Go up to the Lady," they say, " and ask her to write down who she is and what she wants."

Bernadette, not a bit afraid, went right up to the wild rose-tree in which Our Lady was standing, held up her paper and ink bottle, and stood there looking up at the niche. Our Lady smiled. " It is not necessary to write down what I have to say to you. Do me the kindness to come here every day for a fortnight." "Yes, I will," said Bernadette. Then Our Lady added: " And on my part, I promise to make you happy, not in this world but in the next."

Strange promise, that no girl of fourteen would have invented! Promise, too, strangely fulfilled. As we shall see, Bernadette's life was not what we should call a happy one. All her life long she was the victim of continual ill-health. Her chest was weak; she had a chronic asthma, which often caused her most intense suffering, and as she grew up a large tumor formed on her knee, and her bones were attacked by caries. She had also all sorts of external crosses and persecutions to endure, and, moreover, in her own soul there was, to the very end, little of joy and internal consolation. Hers was a dull, monotonous, struggling existence till the very day of her death; matter of fact from first to last, with none of that excitement or enthusiasm, such as is wont to accompany fancied visions and celestial visitations, sprung of an overwrought imagination.

"Ask her," said one of Bernadette's companions, "if she minds our coming with you." "No," was the reply, "they may come if they like." Then the vision disappeared. When the child returned to the town she told her parents that the Lady had made her promise to come to the rock every day for a fortnight. The next day her mother went with her, and a number of other women accompanied her. They all noticed the same wonderful expression that came over the child's features as soon as Our Lady appeared to her.

During the next few days the number of spectators increased. The story spread from mouth to mouth. No one would think that the child was trying to deceive them. She might be under an illusion, the victim of a highly-wrought imagination, but she was no impostor. It was wonderful to see her as she knelt day by day amid the crowd, with a taper in one hand and her rosary in the other, while a religious silence prevailed. Some mysterious influence secured and held all present spellbound. After a few days there was a crowd of some thousands present at the scene long before sunrise. All the best points of observation were occupied by spectators, in spite of the piercing cold. What strange attraction could there be in watching a poor peasant girl kneeling and saying her beads?

Each morning was the same: an increasing crowd, praying, chattering, waiting, struggling for a good place. Then all at once there was a movement in the crowd. "Here she comes!'' and Bernadette walks through the midst of them. They make a way for that poor, humble, insignificant peasant girl, with marks of the greatest respect, the men uncovering their heads as she passes. After her the crowd closes up and follows her, noisy and struggling, till she reaches the Grotto, where she kneels down on a flat piece of rock surrounded by sand, which is always left free, however great the throng, as "Bernadette's place." Then she kneels down and all eyes are fixed upon her. She begins her rosary as if there were no one there. All at once she raises her hands: her appearance changes: the indescribable expression creeps over her face, and a murmur breaks from the crowd, " now she sees her! "Meanwhile she continues her rosary, while those present gaze on her entranced. Her eyes are fixed on the niche in the rock: a sweet smile spreads itself over her countenance, on which love, admiration, joy, respect mingle together, and testify to the presence of one who to the kneeling throng around is invisible. From time to time tears like great drops of dew roll down her cheeks, tears of intense joy, bearing witness to a new, indescribable, and delicious happiness.

What did she see? First of all a soft light illuminating the niche and the rock, then an increasing brightness, then, over the wild rose-tree, appeared the Lady. A Lady of wondrous beauty, with all the freshness of early youth combined with the tenderness of a mother, of unspeakable benevolence in her looks, and a majesty which cannot be described. "Was the Lady as beautiful as certain ladies of remarkable beauty who had come to see her?" The child looked at them with a sort of disdain: "Ever so much more beautiful than they! The Lady, moreover, was surrounded with a circle of light." "What sort of light? Was it like the light of a large fire, or of the stars, or of the moon, or of the sun dazzling us in its mid-day glory?" "No, there was no light on earth resembling it; it was quite different from these and far more beautiful."

During the time of her ecstasy Bernadette saw nothing and heard nothing of what went on around her. If the crowd grew noisy and impatient she was not conscious of it. During that hour of Our Lady's presence she was deaf and blind to all save the vision of the Queen of Heaven.

One day the wind threatened to put out Bernadette's candle; instinctively she put up her hand to shelter the flame. All of a sudden a sweeping gust turned it towards her open hand and the flame passed between her fingers.

"Shell be burnt, poor child!" said the bystanders in pity. But there was not a sign of pain on her face or any shrinking movement of her hand. The fire left no trace: it had not harmed her.

In her ordinary state, Bernadette did not seem to be much preoccupied with this daily favor granted by God to her. She said but little about it, and her parents did not ask her many questions. But when the hour of the apparition drew near, she seemed to be in the possession of a power superior to her own, and the attraction to the Grotto became irresistible. Go to the Grotto she must. When her parents, urged by the police, as we shall presently see, asked her not to go, she told them she could not help going. At last they positively forbade her visits to the Grotto, and on the 22nd she reluctantly obeyed. In the morning she attended the parish school as usual, but in the afternoon she could not resist the secret influence of within that called her, and she went down to the Grotto. As usual she knelt down and said her rosary, but the Lady visited her not.

After this, in reply to threats and prohibitions, she calmly answered, " I can't promise you not to return to the Grotto; something tells me I ought to go; it drives me thither. I must follow the impulse within me." Her parents, recognizing in the influence that urged her one to which they were bound to submit, made no further opposition, Henceforward her mother generally accompanied her to the Grotto.

The next day (Tuesday, the 23d of February), the crowd came down as usual to the banks of the Gave. Bernadette appeared in due time, knelt down with a lighted taper in her hand, and began to say her beads. On this day Our Lady had two communications to make to her--one was a secret message concerning herself which she was told never to reveal, the other was a command which was to be obeyed in a way that even Bernadette never expected. "Go" said Our Lady, "to the priests, and tell them that it is my wish that they should build me a chapel here, and that they ought to come here in procession."

Who that gazes at the magnificent basilica that now adorns the rock of Massabielle, and watches the thousands of picas pilgrims streaming along the road to the Grotto in solemn procession, can fail to recognize the power of Mary's word? Her fiat, now as ever, echoes in Heaven and is obeyed on earth.

One of the following mornings witnessed a new feature in the apparitions. As Bernadette knelt in her ecstasy amid the assembled crowd, all at once she was seen to kiss the ground and then drag herself along on her knees towards the niche, touching the earth from time to time with her lips. She dragged herself up the steep ascent in front of the Grotto, entered it, and remained for a short time immovable, looking up in the direction of the niche. Then she turned to the crowd, drew herself up to her full height, and with wonderful authority and energy cried out:

"You, too, are to kiss the ground!"

Then she knelt down again, and herself set the example. What had Our Lady said to her? She had heard these words, "You will pray God for sinners; you will kiss the earth for the conversion of sinners,"

On several subsequent mornings the, same command was given to Bernadette. On these occasions she described Our Lady's countenance as veiled in an expression of infinite sadness, which, however, did not mar her look of perfect happiness and joy. Once the child kept murmuring, "Penance, penance, penance!" but in general she remained silent throughout her ecstasy.

Thursday, the 25th of February, was one of the most notable days in the history of the Grotto. All of a sudden, in the midst of her ecstasy, she moved as if summoned somewhere, and rising turned her steps towards the corner of the Grotto. Our Lady had said to her: "Go and drink in the spring and wash yourself there, and eat some of the little plant growing there."

The child had seen no spring, and thought it was meant that she should go to the Gave. But with her eyes and her outstretched arm Our Lady pointed to the corner of the Grotto. Bernadette accordingly began to move thither, while the crowd made way for her. A mass of sand and rock blocked up the entrance, and sloped upwards until the level within was six feet above the level of the earth without. She mounted the slope and looked for the spring. But spring there was none, not even a drop of water--only the moist ground with some herbs growing in it.

She looked up at Our Lady, and at a sign from her began to scrape with her fingers in the earth. As she scraped, the hole she made began to fill with muddy water. She looked up again at the vision, and then took some of the water in her hollow hand and tried to drink it. Three times her courage failed her, so dirty was the water; but after another look towards the niche she succeeded in overcoming her repugnance, and swallowed it. Then she stooped down again, and again filling her hand with the dirty water, which was now bubbling up in abundance, she dashed it over her face, and then rose up.

A movement of surprise ran through the crowd. "Look at her! how dirty she is making herself, poor child!"

Bernadette meantime picked some leaves of a sort of cress that was growing in the wet ground, and ate them.

"What is she doing? is she mad?" asked the spectators of each other as they watched her. No, not mad, but humbling herself before the world, doing what was repugnant to nature, and so earning blessings innumerable for all the sinners and sick who were to wash in that wondrous fountain. For this was the miraculous water of Lourdes, now famous throughout the Catholic world. God regarded the humility of His handmaiden, and the flowing water began to stream forth where that poor child's fingers had, in obedience to Our Lady's word, scraped away the earth and sand. Already it had overflowed the little basin she had made, and a little stream began gently to run down the slope from the summit of which it had bubbled up.

The next day the crowd came and Bernadette came, but Our Lady did not appear--a clear sign, if any were wanting, that hers was no imposture or effect of imagination.

During all the remainder of the fourteen days the vision appeared each day at the accustomed hour. Each day the crowd increased, and each day the little stream of water became larger than before. Was there a spring of water there before Bernadette's fingers had scraped at the soil? No one had ever suspected one. Even supposing there had been one (which was very unlikely) was it not a miracle that the poor, ignorant peasant girl should light upon it in so strange a way? Was it not also a miracle that a large, ever-increasing body of water should pour forth from so unexpected a place? People began to say, " There will be some extraordinary virtue in that water."

So thought a good stone-cutter of Lourdes, named Louis Barriette, the sight of one of whose eyes had been entirely destroyed by an explosion in a mine. One day he very sensibly said to himself: "If it is Our Lady who comes to the Grotto, I think she will cure me by means of that water that Bernadette discovered." So he sent his little daughter to get a jug of it, said some prayers, and bathed with the water the eye of which the sight was gone. All of a sudden lie utters a loud cry. He can see as well with this eye as with the one that had never been injured!

He goes out of his house and in the town meets the doctor of Lourdes. "Doctor," he cries, "I am cured!"

"Impossible!" answered Dr. Dojous, "your eye has an organic injury which renders it incurable;" and with these words he takes out his pocket-book and writes down a sentence, which he holds before Barriette's damaged eye, carefully covering the other with his hand.

People began to gather round while the workman with his blind eye reads out loud these words: " Barriette has an incurable amaurosis. He will never recover his sight."

Dr. Dojous was simply stupefied. "Well, that is a real miracle. It upsets all my theories, and I can only confess the presence of a higher power."

The town soon resounds with the story. A miracle has been worked, and it is Our Lady who has worked it, for the sick man was healed by invoking her holy name. Other wonders follow, which space forbids our telling in detail. A woman whose hand had been paralyzed for ten years plunged it into the water and was instantly cured. A little child of two years old was at the point of death. The deadly pallor on its little face showed that all hope was gone. " It is dead/' said its father, "it has already ceased to breathe." The agonized mother, taking it from its cradle, carries it to the newly flowing spring and plunges it into the cold water. " Holy Mother of God, I shall hold my baby here till you cure it." After a short time the child shows signs of life. The happy mother carries it back, rejoicing, but still trembling. But, see! the death pallor is gone, and the tints of health return. It eagerly takes the breast, and two days later is running about perfectly well.

But now the fortnight during which Our Lady has asked for Bernadette's presence at the Grotto is almost over. It is the last morning, and there is an enormous crowd--soldiers, police, government officials, men of science, unbelievers, priests, and pious women without end, all assembled to watch a poor little peasant girl kneeling and saying her beads. Let us hear the testimony of one of the Government officials:--

"I got there," he says, "disposed to laugh heartily at what I regarded as a lot of rubbish. An immense multitude had assembled around the Grotto. I was in the front row when Bernadette arrived. I was close to her, and noticed on her childish features that stamp of sweetness, innocence, and profound repose that had already struck me when she was questioned before the Inspector of Police. She knelt down naturally, without any fuss, just as if she had been alone. She took out her beads and began to pray. Soon her look seemed to receive and reflect an unknown brightness, and became fixed, and fastened itself, radiant with happiness and full of wonder and delight, on the niche in the rock. I looked there also, and saw nothing but the branches of the wild briar. Yet, in the presence of the transformation of that child, all my previous prejudices, philosophical difficulties, preconceived objections fell to the ground at once and gave place to a sentiment that took possession of me in spite of myself. I felt a certitude, I had a sort of intuition that I could not withstand, that some mysterious being was present there. My eyes saw it not, but my intellect, and that of the countless spectators present there, saw it by the interior light of the evidence before us. Yes, I must declare my conviction that the Blessed Virgin was there. Bernadette was suddenly and completely transfigured. She was no longer Bernadette. She was an angel from Heaven, plunged in an ecstasy that words cannot describe. Her face was no longer the same. She opened wide her eyes, insatiate of what they saw; she smiled to one we saw not, and her whole appearance gave a clear notion of ecstatic and intense happiness."

A movement of surprise ran through the crowd. "Look at her! how dirty she is making herself, poor child!"

Bernadette meantime picked some leaves of a sort of cress that was growing in the wet ground, and ate them.

"What is she doing? is she mad?" asked the spectators of each other as they watched her. No, not mad, but humbling herself before the world, doing what was repugnant to nature, and so earning blessings innumerable for all the sinners and sick who were to wash in that wondrous fountain. For this was the miraculous water of Lourdes, now famous throughout the Catholic world. God regarded the humility of His handmaiden, and the flowing water began to stream forth where that poor child's fingers had, in obedience to Our Lady's word, scraped away the earth and sand. Already it had overflowed the little basin she had made, and a little stream began gently to run down the slope from the summit of which it had bubbled up.

The next day the crowd came and Bernadette came, but Our Lady did not appear--a clear sign, if any were wanting, that hers was no imposture or effect of imagination.

During all the remainder of the fourteen days the vision appeared each day at the accustomed hour. Each day the crowd increased, and each day the little stream of water became larger than before. Was there a spring of water there before Bernadette's fingers had scraped at the soil? No one had ever suspected one. Even supposing there had been one (which was very unlikely) was it not a miracle that the poor, ignorant peasant girl should light upon it in so strange a way? Was it not also a miracle that a large, ever-increasing body of water should pour forth from so unexpected a place? People began to say, " There will be some extraordinary virtue in that water."

So thought a good stone-cutter of Lourdes, named Louis Barriette, the sight of one of whose eyes had been entirely destroyed by an explosion in a mine. One day he very sensibly said to himself: "If it is Our Lady who comes to the Grotto, I think she will cure me by means of that water that Bernadette discovered." So he sent his little daughter to get a jug of it, said some prayers, and bathed with the water the eye of which the sight was gone. All of a sudden lie utters a loud cry. He can see as well with this eye as with the one that had never been injured!

He goes out of his house and in the town meets the doctor of Lourdes. "Doctor," he cries, "I am cured!"

"Impossible!" answered Dr. Dojous, "your eye has an organic injury which renders it incurable;" and with these words he takes out his pocket-book and writes down a sentence, which he holds before Barriette's damaged eye, carefully covering the other with his hand.

People began to gather round while the workman with his blind eye reads out loud these words: " Barriette has an incurable amaurosis. He will never recover his sight."

Dr. Dojous was simply stupefied. "Well, that is a real miracle. It upsets all my theories, and I can only confess the presence of a higher power."

The town soon resounds with the story. A miracle has been worked, and it is Our Lady who has worked it, for the sick man was healed by invoking her holy name. Other wonders follow, which space forbids our telling in detail. A woman whose hand had been paralyzed for ten years plunged it into the water and was instantly cured. A little child of two years old was at the point of death. The deadly pallor on its little face showed that all hope was gone. " It is dead/' said its father, "it has already ceased to breathe." The agonized mother, taking it from its cradle, carries it to the newly flowing spring and plunges it into the cold water. " Holy Mother of God, I shall hold my baby here till you cure it." After a short time the child shows signs of life. The happy mother carries it back, rejoicing, but still trembling. But, see! the death pallor is gone, and the tints of health return. It eagerly takes the breast, and two days later is running about perfectly well.

But now the fortnight during which Our Lady has asked for Bernadette's presence at the Grotto is almost over. It is the last morning, and there is an enormous crowd--soldiers, police, government officials, men of science, unbelievers, priests, and pious women without end, all assembled to watch a poor little peasant girl kneeling and saying her beads. Let us hear the testimony of one of the Government officials:--

"I got there," he says, "disposed to laugh heartily at what I regarded as a lot of rubbish. An immense multitude had assembled around the Grotto. I was in the front row when Bernadette arrived. I was close to her, and noticed on her childish features that stamp of sweetness, innocence, and profound repose that had already struck me when she was questioned before the Inspector of Police. She knelt down naturally, without any fuss, just as if she had been alone. She took out her beads and began to pray. Soon her look seemed to receive and reflect an unknown brightness, and became fixed, and fastened itself, radiant with happiness and full of wonder and delight, on the niche in the rock. I looked there also, and saw nothing but the branches of the wild briar. Yet, in the presence of the transformation of that child, all my previous prejudices, philosophical difficulties, preconceived objections fell to the ground at once and gave place to a sentiment that took possession of me in spite of myself. I felt a certitude, I had a sort of intuition that I could not withstand, that some mysterious being was present there. My eyes saw it not, but my intellect, and that of the countless spectators present there, saw it by the interior light of the evidence before us. Yes, I must declare my conviction that the Blessed Virgin was there. Bernadette was suddenly and completely transfigured. She was no longer Bernadette. She was an angel from Heaven, plunged in an ecstasy that words cannot describe. Her face was no longer the same. She opened wide her eyes, insatiate of what they saw; she smiled to one we saw not, and her whole appearance gave a clear notion of ecstatic and intense happiness."

At last the fourteen days during which Our Lady had asked Bernadette to present herself at the Grotto were over. On the last morning (the 4th of March) an enormous crowd had collected long before daybreak. There was great excitement among the people. "Something will happen to that child," said the wiseacres of Lourdes; " she will be carried away by Our Lady, or fall dead on the spot." Her parents were quite frightened; still they determined that she should go all the same. So Bernadette, as usual, heard Mass, and came down to the Grotto. Officers of police, gendarmes, soldiers, were there to keep order in the assembled multitude. A gendarme was waiting for Bernadette, with a drawn sword, to make way for her through the crowd; without this it would have been almost impossible for her to get through the dense mass that had assembled. She knelt down as usual, and soon the vision appeared to her. She drank at the fountain, kissed the ground as usual. Our Lady smiled her farewell, and the vision disappeared. Bernadette got up and went home, and the crowd gradually dispersed.

The next day Bernadette came as usual, and the spectators came too. She knelt and said her beads, but no apparition. The same thing on the next day, and the next. No voice within her summoned her to the Grotto: her visions were apparently at an end. But on the 25th of March (Lady Day) she felt once more the internal impulse. Joyous she hastened to the Grotto, knelt down, and had scarce begun her Rosary when a sudden start and the transformation of her features announced that the Lady had reappeared. As soon as she saw her, in obedience to the instruction given her by the parish priest, she asked her to tell her her name. The answer was a smile. " Madam," asked Bernadette again, "will you tell me who you are? " Our Lady raised her hands and eyes to Heaven, and answered, "I am the Immaculate Conception" (2) and then instantly disappeared. The ignorant child did not know what the words meant, but on her way back to the town she repeated them continually, lest she should forget them. Instead of going home she went straight to the presbytery, and learned from the priest that the words she had heard were those that proclaim the singular privilege that has raised Mary above all the saints and angels on earth and in Heaven. Radiant with joy, she carries home the news that the Lady who has appeared to her is indeed, without doubt, the Holy Mother of God.

The next twelve days were a blank for Bernardette, as far as any vision was concerned; but on the 7th of April (Wednesday in Easter week) the inner voice once more informed her that Our Lady was going to visit her that day. Arrived at the Grotto, she was not disappointed; she had no sooner commenced her Rosary than Our Lady appeared. On this occasion there was a fresh wonder.

During the ecstasy she had a lighted candle in her hand, which she was resting on the rock in front of her, and, absorbed in what she saw, she gradually raised the hand that was holding the candle and lightly joined her two hands immediately above the flame. The flame passed through her fingers, its summit appearing above them, but she moved not, and gave no sign of pain. A cry ran through the crowd: " She is burning herself! " Still Bernadette moved not.

A doctor was standing close by. He took out his watch to see how long the wonder would last. For more than a quarter of an hour the flame continued to burn on, and her hands remained in the midst of it. No sign of pain--the same sweet smile playing on her lips. A thousand eyes watched the scene, and distinctly saw the flame passing through her fingers.

At length her hands opened. The doctor took hold of them, and examined them. They were quite white, neither scorched nor blackened by the flame!

Then softly through the crowd went the whisper, "A miracle, a miracle!"

A few moments after Bernadette came out of her ecstasy, and the doctor, taking hold of her hand, quietly held it over the candle.

"You're hurting me! you're burning me!" she cried, pulling her hand away.

There could be no doubt, after this, about the miracle.

Here the curtain falls on what may be called Our Lady's public apparitions to Bernadette. Once again she saw her, but long after, and when she was almost alone.

But we must now turn to the contradictions which every work of God has to encounter. While there was a continually increasing number of those whose prudent reserve and wise discretion at first had gradually made way for a firm belief in the supernatural character of the wonders wrought, there was a still larger number who were determined to be skeptical. At first they accused the child of being a skilful actor and hypocrite, and when such an hypothesis was proved by facts to be impossible, they fell back on the theory of hallucination. Bernadette was a poor silly thing, with feeble powers, cataleptic tendencies, and strong imagination. Unfortunately, the doctors who examined her said she had no sort of disposition to catalepsy, that she was remarkably matter-of-fact, sensible, and very unimaginative.

The police of Lourdes were decidedly on the side of the opposition, and thought it their duty to throw all the obstacles they could in the way of the apparitions at the Grotto. Bernadette was threatened, and then her parents. The authorities talked about imprisonment, and said that the crowds that assembled each morning threatened to disturb the peace of the town.

The Prefect of the department, who was a good Catholic, was at first under the impression that the whole business was an imposture, and that real harm would be done to religion if it were allowed to continue. This gave the local police fresh courage in their persecution of Bernadette. One day the inspector and sergeant of police placed themselves at her side, and attempted to disturb her. But her godmother compelled them to desist: the child was doing no wrong, and they had no right to interfere.

To keep up the charge of fraud became impossible, so they sent some doctors to examine her, with the intention of sending her to a lunatic asylum, if any trace of madness could be discovered in her. But the medical reports declared her intellect to be perfectly clear and sound. Thus their attempt to take any personal measures against Bernadette failed for the time.

But if Bernadette could not be assailed, they could at least prevent the growing superstition that was taking place at Lourdes. During the month of May succeeding the apparitions, crowds of pilgrims had resorted to the Grotto. The crevices in the rock were filled with little statues and bouquets of flowers, and the Grotto was lighted up with a continual illumination of wax candles. On the 8th of June, the police carried off all the objects that had been deposited in the Grotto, and boarded it up. On the rock a notice was put up, No one is allowed to enter these grounds (Defense d'entrer sur cette propriete). A number of police were posted around the Grotto to enforce this notice, but pious people managed to evade it, and though there were a good many summonses issued, no one was actually punished for disobeying it.

One morning, however, when the first policeman came down to his post, he found to his dismay that the Government hoarding had been broken down during the night, and the planks composing it laid in a great heap in front of the Grotto. There was no trace of the offenders, who consisted of workmen belonging to Lourdes, who had watched their opportunity, and before the dawn had completed the work of destruction. The authorities were not a little annoyed, and promptly replaced the barrier, and for several nights watched for any intruders. But all in vain, and so they left off their nocturnal guard. The very next morning the hoarding had once more disappeared. This time the prudent workmen had not given the adversary a chance of rebuilding with the same materials. The planks had all been thrown into the Gave, and by the time that the police came to the place, had been carried miles down the stream by the obliging waters.

Meanwhile, an ever-increasing stream of pilgrims came to Lourdes, and cures which could not be explained by any natural laws began to be multiplied. It was impossible to deny the facts. Bernadette was summoned before the Prefect of Police, questioned, cross-questioned, threatened with prison. Every means was taken to frighten her, to discourage her, to shake her calm, clear, oft-repeated assertion of the reality of what she saw. She remained perfectly quiet and at her ease throughout all the vexatious interrogations and menaces of punishment. "They won't do what they say," she used to repeat. "God is stronger than they. Don't be afraid! If they put me in prison, they will only have to let me out again."

The Prefect at length, foiled in his direct attempts, had recourse to the Bishop of Tarbes, and urged upon him a judicial inquiry, to put an end to this nonsense, if nonsense it was. At the same time the popular voice and a number of the clergy begged his Lordship, for the honor of Our Lady, and the promotion of devotion to her, to issue a commission to investigate all that had happened. But the prudent and wise Prelate was not going to act in a hurry--he watched and waited. Skeptical at first as to the reality of the apparition, he had gradually been won over by the irresistible force of the accumulating evidence in favor of it, but nevertheless he still waited. May, June, July passed, but he refused to take any steps.

From the 5th of April till the 16th of July, Bernadette had visited the scene of the apparitions nearly every day, but she had never felt the interior impulse which was the precursor of a visit from Our Lady, and had simply knelt and said her beads among the other pilgrims. But on the 16th of July, the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the mysterious attraction once more called her to the Grotto. It was closed at the time by the police, and Bernadette even more than others would be promptly sent back. So she crossed the Gave, and went down through the meadows on the other side to the bank of the river exactly opposite the Grotto, and there knelt down with two women who accompanied her, to say her Rosary. Presently she made a movement which made her companions suspect that she saw the vision once again. It was getting dark, so one of them lighted a candle they had brought with them, and they saw the same indications of her ecstasy that had been often observed before--the kindling brightness of her eye, the supernatural beauty of expression, the radiant transparency of her countenance. They watched her in silence for a quarter of an hour, while the child was drinking of that delicious draught of heavenly sweetness of which the Wise Man tells in the Canticle of Canticles: " Drink, O my friends, and be inebriated, my dearly beloved. (3) Never, said Bernadette, had Our Lady appeared so glorious as then, the light around her never so dazzling, her face never so beautiful and majestic. The moment the first ray of this heavenly light fell upon her, all was forgotten--the river, the Grotto, the barrier, all around her simply disappeared. She was absorbed in the contemplation of the celestial vision; for her there existed nothing else on earth save the apparition that stood before her.

But it was the last time. Never again, until she beheld her in the Paradise of God, was Bernadette to be favored with another sight of the Queen of Heaven.

The next day Bernadette came as usual, and the spectators came too. She knelt and said her beads, but no apparition. The same thing on the next day, and the next. No voice within her summoned her to the Grotto: her visions were apparently at an end. But on the 25th of March (Lady Day) she felt once more the internal impulse. Joyous she hastened to the Grotto, knelt down, and had scarce begun her Rosary when a sudden start and the transformation of her features announced that the Lady had reappeared. As soon as she saw her, in obedience to the instruction given her by the parish priest, she asked her to tell her her name. The answer was a smile. " Madam," asked Bernadette again, "will you tell me who you are? " Our Lady raised her hands and eyes to Heaven, and answered, "I am the Immaculate Conception" (2) and then instantly disappeared. The ignorant child did not know what the words meant, but on her way back to the town she repeated them continually, lest she should forget them. Instead of going home she went straight to the presbytery, and learned from the priest that the words she had heard were those that proclaim the singular privilege that has raised Mary above all the saints and angels on earth and in Heaven. Radiant with joy, she carries home the news that the Lady who has appeared to her is indeed, without doubt, the Holy Mother of God.

The next twelve days were a blank for Bernardette, as far as any vision was concerned; but on the 7th of April (Wednesday in Easter week) the inner voice once more informed her that Our Lady was going to visit her that day. Arrived at the Grotto, she was not disappointed; she had no sooner commenced her Rosary than Our Lady appeared. On this occasion there was a fresh wonder.

During the ecstasy she had a lighted candle in her hand, which she was resting on the rock in front of her, and, absorbed in what she saw, she gradually raised the hand that was holding the candle and lightly joined her two hands immediately above the flame. The flame passed through her fingers, its summit appearing above them, but she moved not, and gave no sign of pain. A cry ran through the crowd: " She is burning herself! " Still Bernadette moved not.

A doctor was standing close by. He took out his watch to see how long the wonder would last. For more than a quarter of an hour the flame continued to burn on, and her hands remained in the midst of it. No sign of pain--the same sweet smile playing on her lips. A thousand eyes watched the scene, and distinctly saw the flame passing through her fingers.

At length her hands opened. The doctor took hold of them, and examined them. They were quite white, neither scorched nor blackened by the flame!

Then softly through the crowd went the whisper, "A miracle, a miracle!"

A few moments after Bernadette came out of her ecstasy, and the doctor, taking hold of her hand, quietly held it over the candle.

"You're hurting me! you're burning me!" she cried, pulling her hand away.

There could be no doubt, after this, about the miracle.

Here the curtain falls on what may be called Our Lady's public apparitions to Bernadette. Once again she saw her, but long after, and when she was almost alone.

But we must now turn to the contradictions which every work of God has to encounter. While there was a continually increasing number of those whose prudent reserve and wise discretion at first had gradually made way for a firm belief in the supernatural character of the wonders wrought, there was a still larger number who were determined to be skeptical. At first they accused the child of being a skilful actor and hypocrite, and when such an hypothesis was proved by facts to be impossible, they fell back on the theory of hallucination. Bernadette was a poor silly thing, with feeble powers, cataleptic tendencies, and strong imagination. Unfortunately, the doctors who examined her said she had no sort of disposition to catalepsy, that she was remarkably matter-of-fact, sensible, and very unimaginative.

The police of Lourdes were decidedly on the side of the opposition, and thought it their duty to throw all the obstacles they could in the way of the apparitions at the Grotto. Bernadette was threatened, and then her parents. The authorities talked about imprisonment, and said that the crowds that assembled each morning threatened to disturb the peace of the town.

The Prefect of the department, who was a good Catholic, was at first under the impression that the whole business was an imposture, and that real harm would be done to religion if it were allowed to continue. This gave the local police fresh courage in their persecution of Bernadette. One day the inspector and sergeant of police placed themselves at her side, and attempted to disturb her. But her godmother compelled them to desist: the child was doing no wrong, and they had no right to interfere.

To keep up the charge of fraud became impossible, so they sent some doctors to examine her, with the intention of sending her to a lunatic asylum, if any trace of madness could be discovered in her. But the medical reports declared her intellect to be perfectly clear and sound. Thus their attempt to take any personal measures against Bernadette failed for the time.

But if Bernadette could not be assailed, they could at least prevent the growing superstition that was taking place at Lourdes. During the month of May succeeding the apparitions, crowds of pilgrims had resorted to the Grotto. The crevices in the rock were filled with little statues and bouquets of flowers, and the Grotto was lighted up with a continual illumination of wax candles. On the 8th of June, the police carried off all the objects that had been deposited in the Grotto, and boarded it up. On the rock a notice was put up, No one is allowed to enter these grounds (Defense d'entrer sur cette propriete). A number of police were posted around the Grotto to enforce this notice, but pious people managed to evade it, and though there were a good many summonses issued, no one was actually punished for disobeying it.

One morning, however, when the first policeman came down to his post, he found to his dismay that the Government hoarding had been broken down during the night, and the planks composing it laid in a great heap in front of the Grotto. There was no trace of the offenders, who consisted of workmen belonging to Lourdes, who had watched their opportunity, and before the dawn had completed the work of destruction. The authorities were not a little annoyed, and promptly replaced the barrier, and for several nights watched for any intruders. But all in vain, and so they left off their nocturnal guard. The very next morning the hoarding had once more disappeared. This time the prudent workmen had not given the adversary a chance of rebuilding with the same materials. The planks had all been thrown into the Gave, and by the time that the police came to the place, had been carried miles down the stream by the obliging waters.

Meanwhile, an ever-increasing stream of pilgrims came to Lourdes, and cures which could not be explained by any natural laws began to be multiplied. It was impossible to deny the facts. Bernadette was summoned before the Prefect of Police, questioned, cross-questioned, threatened with prison. Every means was taken to frighten her, to discourage her, to shake her calm, clear, oft-repeated assertion of the reality of what she saw. She remained perfectly quiet and at her ease throughout all the vexatious interrogations and menaces of punishment. "They won't do what they say," she used to repeat. "God is stronger than they. Don't be afraid! If they put me in prison, they will only have to let me out again."

The Prefect at length, foiled in his direct attempts, had recourse to the Bishop of Tarbes, and urged upon him a judicial inquiry, to put an end to this nonsense, if nonsense it was. At the same time the popular voice and a number of the clergy begged his Lordship, for the honor of Our Lady, and the promotion of devotion to her, to issue a commission to investigate all that had happened. But the prudent and wise Prelate was not going to act in a hurry--he watched and waited. Skeptical at first as to the reality of the apparition, he had gradually been won over by the irresistible force of the accumulating evidence in favor of it, but nevertheless he still waited. May, June, July passed, but he refused to take any steps.

From the 5th of April till the 16th of July, Bernadette had visited the scene of the apparitions nearly every day, but she had never felt the interior impulse which was the precursor of a visit from Our Lady, and had simply knelt and said her beads among the other pilgrims. But on the 16th of July, the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the mysterious attraction once more called her to the Grotto. It was closed at the time by the police, and Bernadette even more than others would be promptly sent back. So she crossed the Gave, and went down through the meadows on the other side to the bank of the river exactly opposite the Grotto, and there knelt down with two women who accompanied her, to say her Rosary. Presently she made a movement which made her companions suspect that she saw the vision once again. It was getting dark, so one of them lighted a candle they had brought with them, and they saw the same indications of her ecstasy that had been often observed before--the kindling brightness of her eye, the supernatural beauty of expression, the radiant transparency of her countenance. They watched her in silence for a quarter of an hour, while the child was drinking of that delicious draught of heavenly sweetness of which the Wise Man tells in the Canticle of Canticles: " Drink, O my friends, and be inebriated, my dearly beloved. (3) Never, said Bernadette, had Our Lady appeared so glorious as then, the light around her never so dazzling, her face never so beautiful and majestic. The moment the first ray of this heavenly light fell upon her, all was forgotten--the river, the Grotto, the barrier, all around her simply disappeared. She was absorbed in the contemplation of the celestial vision; for her there existed nothing else on earth save the apparition that stood before her.

But it was the last time. Never again, until she beheld her in the Paradise of God, was Bernadette to be favored with another sight of the Queen of Heaven.

The Subsequent History of Bernadette Soubirous

by Richard F. Clarke, S.J., 1888

July 28, 1858, the Bishop of Tarbes issued a pastoral (mandement) in which he said that ecclesiastical authority was going to occupy itself with the Grotto at Lourdes, and that a commission was charged to make an official inquiry. The commission had for its object to furnish an answer to the following questions:

When the Commission was authorized by the Bishop, he had hoped that the civil authorities would leave the matter in his hands. But the Prefect had by this time made up his mind that the whole business was a mere imposture, or superstition, and continued to persecute Bernadette and watch the pilgrims as much as ever. Happily, however, a higher authority interfered. The Emperor heard the story, and at once sent word (October, 1858) that all opposition was to cease. Thenceforward barriers, boarding, police interference, summonses to trespassers, were all at an end. Bernadette, her parents, and the pilgrims, were left in peace.

The Commission continued its labors for nearly three years. During the first two years Bernadette continued to go to the parish school, and at the end of that time (she was then sixteen years old) was received as a boarder into the Convent of the Sisters of Nevers. It is needless to say that she had innumerable visitors. What was the general impression she made upon them?

The Heavenly Visitation she had enjoyed had not changed her to outward appearance She was still rather below the average in intelligence, very wanting in imagination, and not at all expansive. She had no power to describe what she saw or to interest visitors. "When she told her story she did so with wonderful conciseness and almost coldness. People sometimes said to her, "How can you talk so coldly of such wonderful things?" Yet she was gentle, good, simple, innocent, and some visitors were charmed with her. If she was questioned, there was something in her answers that showed how sure she was of her facts. Questions, instead of embarrassing her, seemed to make her more at her ease. But it was when any one attempted to argue the point with her, and raised all kinds of objections to what she said, that Bernadette showed to the best advantage. That passionless, matter-of-fact child seemed to be no longer the same person when she had to defend the truth of her story, or when the honor of Our Lady of Lourdes seemed to her to be at stake. Contradiction roused her: she always had plenty to answer, and the readiness and justice of her replies were most remarkable. In spite of her mediocre intelligence, she often astonished and put to silence clever men who cross-questioned her. They "could not resist the spirit and the wisdom with which she spoke."

There were other features in her conduct that were very much in her favor. Never would she take any sort of gift for herself or for any of her family. They were miserably poor, and visitors offered them money without end, but it was invariably refused. Indeed, it is not unlikely that this prohibition to receive anything was one of the commands imposed upon her by Our Lady.

Her early simplicity, too, was in no way affected by the crowds who sought her. If she had not been under the special guidance of God, she could not have failed to have her head turned by the notice taken of her and the flattery that was poured into her ear. People called her a saint; asked her to put her hand on pious objects, and so make relics of them; but she always answered, "Why, I can't bless anything." It all made no impression upon her, and she never seemed to take to herself any of the compliments paid her, but all went to Our Lady, who had regarded the humility of her handmaiden.

Another curious fact told very much in her favor, and was strong evidence of the reality of her visions. Contact with her seemed to kindle devotion, and had a wonderful power to strengthen in her visitors their faith in the supernatural. Men of the world who listened to her story could not help believing, often in spite of themselves. "I don't know about the miracles," said a Protestant magistrate who visited Lourdes; " it is that child who astonishes me and goes to my heart. I am sure there must be something in her story." In fact, Bernadette, the ignorant, matter-of-fact, rather dull, undemonstrative Bernadette, exercised a regular apostolate in the impulse she gave to devotion to Our Lady and to belief in the supernatural.

We must hasten on. The Episcopal Commission did its work most thoroughly, and at length made its formal report to the Bishop. He took some months to consider it, but at length, on January 18, 1862, was published the Pastoral of the Bishop of Tarbes respecting the apparition at Lourdes. We regret that our space does not permit us to give it in full. Enough to say that it discusses, with admirable clearness and good sense, apparitions, miracles, pilgrims, Bernadette, and sets forward the following as the result of the official investigation made by the Commission:

"We give sentence (nous jugeons) that Mary Immaculate, Mother of God, has really appeared to Bernadette Soubirous on February 11, 1858, and the following days, to the number of eighteen times, in the Grotto of Massabielle, near the town of Lourdes; that this apparition carries with it all the marks of truth, and that the faithful have good ground (sontfondes) for believing it certain."

We left Bernadette, at the age of sixteen, confided to the care of the Sisters of Nevers. In their convent she remained as a boarder till she was twenty-two. She was allowed to receive visitors in the parlor there. Her life was, during a greater part of the year, nothing but a series of receptions. She was at the beck and call of anyone who came to see her. On feast-days it was with some difficulty that she got time for her meals. She did not like the publicity that was forced upon her, and got away as soon as she could. She had to give up all her free time; the continual talking was painful to her. She had poor health and a weak chest. Yet she knew that she was doing God's will. She never complained, she never refused to see those who asked for her. The only sign of her dislike for her continual flow of visitors was a slight shrug of the shoulders when a new visitor was unexpectedly announced. But her time and strength were well spent; she was accomplishing her mission; she had become the apostle of Mary Immaculate.

But the time was drawing near when Our Lord was calling her to a higher life. In 1863, Mgr. Forbade, Bishop of Nevers, to whose jurisdiction the Sisters of Nevers were subject, came to Lourdes and asked to see Bernadette. She was in the kitchen, scraping carrots for the dinner of the community, sitting on a stool in the corner of the fire-place. The Bishop sent for her after dinner, and after talking a little about the apparitions, asked her what she was going to do with herself.

"Nothing," was her answer.

"My dear child, you must do something in the world."

"Why, lam with these good Sisters, and I'm quite content."

"I have no doubt you are, but you can't remain here always. They only took you for a time, out of charity."

"Why can't I stay here always?"

"Because you are not a Sister and not a servant."

"I don't think I should do for a Sister. I have no dowry, and I am no good. I know nothing, and am good for nothing."

"You do not appreciate your talents. I saw this morning that you are good for something."

"Good for what? "

"Why, for scraping carrots!" answered the Bishop, seriously.

Bernadette burst out laughing. "That isn't very difficult!"

"Never mind; if God gives you a vocation, the Sisters will find work for you, and in the novitiate will teach you to do a number of things of which you are ignorant at present.

"Well, I'll think about it."

A year later Bernadette asked to be admitted to the novitiate. Her entrance was put off for two years on account of the miserable state of her health. She had always been a sufferer, her incurable maladies preyed without ceasing on her feeble frame, and from time to time there supervened crises which brought her to the door of death. But in July, 1866, it was decided not to keep her waiting any longer, and on the 8th she was admitted into the novitiate.

The main feature of her novitiate was her total silence respecting the apparitions of Lourdes among her fellow-novices. They had been told not to speak to her on the subject, and though many of them would fain have questioned her, yet they faithfully obeyed the injunction given them. Bernadette herself never broached the subject, and it was only when one of her Superiors spoke to her about it, or some privileged visitor, that anyone could have discovered that this ordinary sort of novice, about whom there was nothing remarkable except her constant sickness, was one who had received from Heaven favors beyond compare.

Bernadette was regular and edifying, but just like the rest as far as externals went. No ecstasies, no wonderful gift of prayer, no outward marks of extraordinary piety. Several times the Bishop of Nevers asked her, "Tell me, Bernadette, have you seen Our Lady again since the last of those visions by the rock of Massabielle, or have you received any other extraordinary graces?"--" No," was her invariable answer, "up to now I am just the same as anybody else."--"Yet," adds the Bishop, " she was not just the same as anybody else. The most marked feature in her was her desire to live unknown and to be counted as a nobody. This is rare enough, even among souls that tend to perfection. No one put into practice better than Bernadette that beautiful precept of the Imitation, Love to be unknown and esteemed of no account." This is high praise from the mouth of the Prelate who was the Superior of the whole community. What impostor, nay, what hysterical or imaginative enthusiast, would have been willing thus to sink into obscurity and oblivion? It shows a strange ignorance of human nature to believe that one who was laboring under the delusions of an overwrought fancy would consent to be snuffed out, nay, would desire above all things to disappear, and never be remembered more by the world that had once run after her as a saint.